“Today, no music,” David Lynch declared during his daily weather report posted today on YouTube, where he typically accompanies the Los Angeles forecast with a song currently spotlighted on his mental playlist. It wasn’t long after that news began to circulate online regarding Lynch’s longtime cherished collaborator, Angelo Badalamenti, one of the all-time greatest composers of film and television, who reportedly passed away yesterday at the age of 85. The news was confirmed by multiple family members, including a great nephew of Angelo’s—credited as @spicey_ghost on Instagram—who wrote in a post that his great uncle “had crossed the barrier onto another plane of existence,” while mentioning his relationships and collaborations with “David Bowie, Michael Jackson, Paul McCartney, Nina Simone, Julee Cruise, Isabelle Rossellini, Dolores O’Riordan, Anthrax, Dokken, Eli Roth and especially David Lynch.” The nephew went on to write that Angelo “has always been the most interesting man in the world to me. A true musical and artistic inspiration for me and countless others. Stayed true to his roots and family, never leaving North Jersey for LA. Not to mention the casual but mind blowing stories he never ran out of. He will truly be missed by many.”

2022 had already proven to be a crushing one for admirers of Lynch’s oeuvre, with the iconic singer of “Twin Peaks,” Julee Cruise, passing in June, and the groundbreaking program’s beloved actor, Al Srobel (renowned for his ever-evolving portrayal of “the one armed man,” Philip Gerard), leaving our world earlier this month. Badalamenti and I shared a birthday, March 22nd, and it was in the year of my birth, 1986, that the composer forged his first phenomenally successful collaboration with Lynch in the director’s fourth feature, “Blue Velvet.” The pervasive sense of unease in his score, echoing the unseemly terrors young Jeffrey (Kyle Maclachlan) uncovers in his deceptively innocent town, does occasionally pause for moments of pure, arresting beauty, many of them involving Jeffrey’s girlfriend, Sandy (Laura Dern). Whether she’s stepping out of the darkness or delivering her hopeful monologue about the robins, Sandy is the score’s ray of light, which contrasts with the melancholy glow of Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini), whose crooning of the title tune is accompanied in the film by Badalamenti himself on the piano.

This landmark began a decades-long teaming of director and composer that rivaled the genius of Hitchcock and Herrmann, Spielberg and Williams, Burton and Elfman. Thanks to Daniel Knox’s masterfully curated David Lynch retrospective held earlier this year at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, I was able to view some of their lesser known efforts in a way they are never shown: on a big screen and with an engaged crowd. 1990’s “Industrial Symphony No. 12: The Dream of the Brokenhearted,” featuring the ever-ethereal Cruise, expanded on the vulnerable soul of Badalamenti’ work in that year’s Palme d’Or winner, “Wild at Heart,” the Lynch picture that drew criticism for its graphic violence. Yet perhaps the most memorable moment in that film is when its lovers on the run, Sailor (Nicholas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern), stop their car until they can find anything on the radio aside from depressingly vile news. They eventually land on their favorite group, Slaughterhouse, and as they rock out to the chaotic vocals, the camera pans up to the setting sun, as a lush swell from Badalamenti’s score fills the soundtrack.

Of course, the themes Badalamenti wrote for “Twin Peaks” across its three seasons conjure instant imagery in one’s imagination: the Man From Another Place (Michael J. Anderson) snapping away to “Dance of the Dream Man,” Audrey Horne (Sheriluyn Fenn) swaying to a melody only she can seem to hear in “Audrey’s Theme,” Sarah Palmer (Grace Zabriskie) convulsing with sobs upon learning the untimely fate of her daughter, Laura (Sheryl Lee), as “Laura’s Theme” blossoms like a mournful flower. One of Badalamenti’s last public statements was a quote he gave to author Scott Ryan for his book, Fire Walk With Me: Your Laura Disappeared, commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of Lynch’s long misunderstood 1992 film, “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.” Badalamenti wrote that Ryan’s “writing and understanding of my music is unreal,” as evidenced in the author’s description of the film’s entrancing opening theme. “We have sex from the trumpet, fear from the synth and rock ’n’ roll from the plucking bass,” he wrote. “What do you get when you mix sex, fear and rock ’n’ roll together? You get Laura Palmer.”

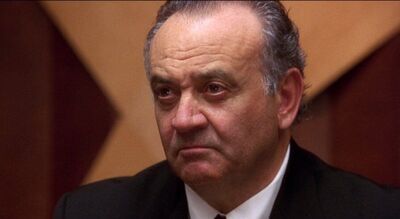

Deserving of equal attention is Badalamenti’s scores for two short-lived Lynch projects, the 1992 sitcom on the madness of the television industry, “On the Air,” and the 1993 HBO series, “Hotel Room,” a striking precursor to “Room 104,” the best episode of which features young Alicia Witt, who delivers a tour de force performances opposite Crispin Glover. Badalamenti collaborated with Lynch on numerous other projects, such as 1997’s deeply scary psychological portrait, “Lost Highway,” and 2002’s nightmarish web series, “Rabbits,” which was eventually woven into the fabric of Lynch’s 2006 abstract epic, “INLAND EMPIRE.” In 1999, Badalamenti composed the music for Lynch’s “Mulholland Dr.”, a failed TV pilot that the director turned two years later into a film, which stands today as my all-time favorite cinematic work (it recently cracked the top ten of Sight & Sound’s latest poll). His scoring of the scene where a sweating Patrick Fischler comes face to face with the dreaded Man Behind Winkies (Bonnie Aarons of “The Nun”) never ceases to cause an audience to leap from their seats, just as his atonal burst does in “Wild at Heart,” signaling the moment Lula’s mom (Diane Ladd) turns to reveal her tortured face covered in lipstick. Badalamenti is equally fearsome and oddly hilarious in his cameo as one of the thuggish suits in “Mulholland Dr.” who swoop in to take ownership of a director’s film, all the while criticizing the coffee offered to them in the most grotesque manner imaginable.

Badalamenti’s talent was not at all confined to the work of Lynch. In a career that spanned six decades, he provided the music for such notable films as “A Nightmare On Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors,” “National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation,” “Holy Smoke,” “Secretary,” “Auto Focus,” “Cabin Fever” and “A Very Long Engagement.” Yet my favorite Badalamenti score, and the one most deserving of a vinyl release, is the one he composed for Lynch’s 1999 masterpiece, “The Straight Story.” Based on the real life story of Alvin Straight, who journeyed from Iowa to Wisconsin on his riding mower to visit his ailing, estranged brother, the film features the final performance of stuntman-turned-brilliant character actor Richard Farnsworth as the Alvin and the final lensing of master cinematographer Freddie Francis (“The Innocents,” “The Elephant Man”). The film’s score engineer and re-recording mixer, John Neff, told me earlier this year in an interview how he recorded the score, mixed it, and then mixed it into the film in 5.1 surround. “On January 30th, 1999, we had fourteen string players and three guitar players in David’s studio, and recorded the score for the film in one twelve-hour day,” Neff recalled. “It was my first orchestral score recording in all those years of working in the studio, and it worked out pretty well. I’m very happy with it.”

The soundtrack album, which I still own on CD, accompanied my family on various road trips to visit my great uncle Chuck, whose spirit is akin to that of Alvin, in Lowpoint, Illinois. Roger Ebert beautifully captured the tone of Badalamenti’s score in his four-star review, writing, “There are fields of waving corn and grain here, and rivers and woods and little bed barns, but on the soundtrack the wind whispering in the trees plays a sad and lonely song, and we are reminded not of the fields we drive past on our way to picnics, but on our way to funerals, on autumn days when the roads are empty.” Of all the tracks on that album, the one I treasure the most is “Rose’s Theme,” which we first hear as Alvin and his devoted daughter Rose (Sissy Spacek) savor a night sky filled with stars. The theme tells a more painful tune later on, as we learn of the tragedy spurred by a fire—a recurring presence in Lynch’s work—that stealthily haunts Rose as she stares out the window. And then we hear it again during the film’s glorious final moments of wordless majesty, articulating with perfectly pitched notes what dialogue never could. This melody has played in my mind at countless point throughout my life whenever I have felt a true sense of peace. Today, I wish Angelo that peace.

0 Commentaires